Louise Otting, Alastair Dunning, January 2024

In read and publish deals, the read part costs a lot more than the publish part.

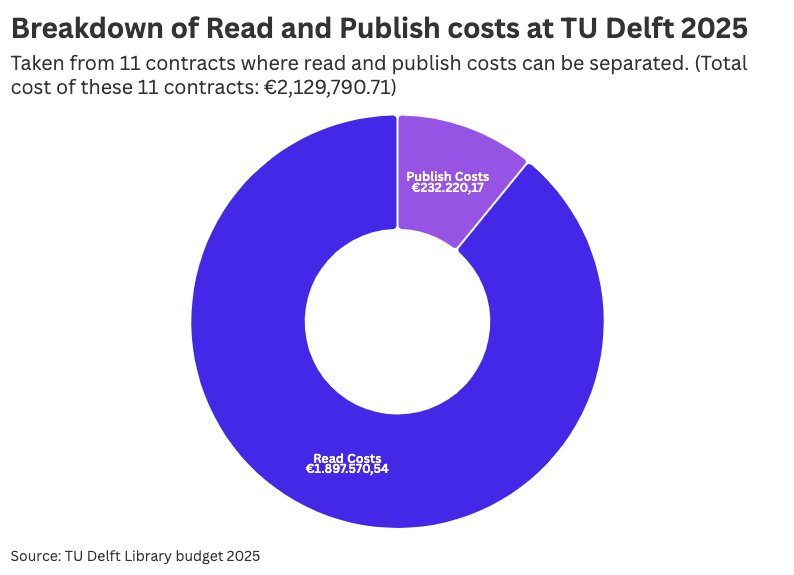

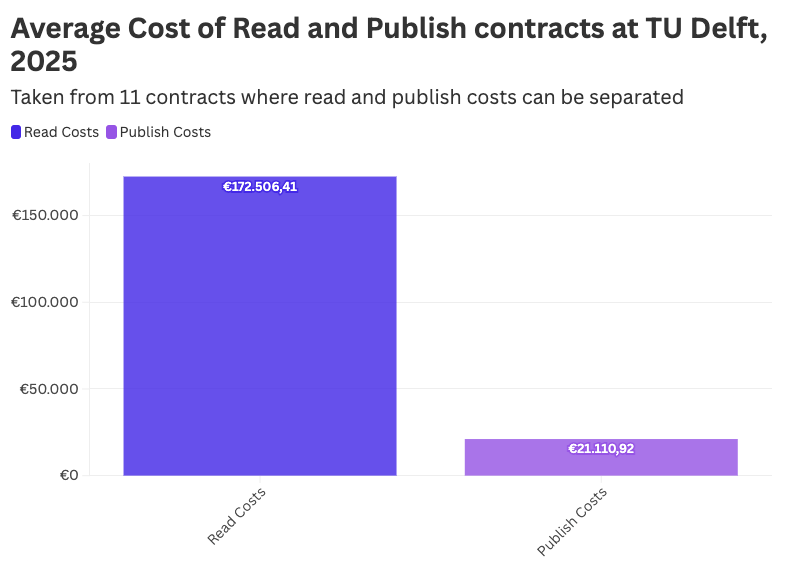

Our analysis of 11 read and publish deals for 2025 at TU Delft showed that just 11% of the annual costs were assigned to the publish costs.

For each individual read and publish contract, the amount paid for the publish part varies from 35% to 1%. It’s notable for nearly all the larger contracts (where TU Delft pays more than 250k per year), the figure falls well under 10% – in one contract, the publish costs are around 1%.

Background Data

The analysis was possible because of a tax quirk in the Dutch value added tax (the BTW, Belasting over de Toegevoegde Waarde). Books and periodicals to be read are charged at 9%. But publishing is considered a service and therefore charged at 21%.

Therefore some, but not all, publishers split their costs into separate invoices. It must also be noted that how this split is arrived at somewhat arbitrary.

Publishers based in the Netherlands have tended to decide on the split themselves. For publishers based outside the Netherlands, SURF (that acts as the consortium lead on behalf of Dutch universities and other knowledge institutions) makes the initial decision. This is based on the costs for reading before the R&P deal. However, there are an increasing number of non-Dutch publishers that make the decision on the split themselves.

Implications

Much of the criticism of read and publish deals has been at lack of transparency in the costs. What are universities actually paying for? And if we break up read and publish deals what will the costs be?

From an economic perspective, it makes sense that the majority of the costs are placed at the 9% tax rate. Universities have less to pay, and therefore are more likely to purchase.

However, it would be naive to assume that universities could split the current contracts and choose to, for example, only pay for publish contracts.

Any university that attempts to split read and publishing contracts is very unlikely to find the existing tariff for publishing continues. Publishers will claim they are helping to work more cheaply because of the very fact that read and publish are bundled together. Split them up, publishers will say, and the cost will rise.

But if the cost of a separate publish only deal does rise, the university is again obliged to ask – what exactly is it universities are paying for?